24x15.5cm Classic Cyanotype from TruNeg Negative

Copy of 28 x 18.1 cm Carbon Print with Oxide Black pigment made with a TruNeg Negative

The Authentic Digital Negative

The True Digital Negative

Before going into why the editing program’s negative doesn’t work, a true digital negative needs to be defined.

By convention, the standard photographic negative, whether analog or digital, records a brightness range of eight stops, that is, the brightness doubles eight times, once for each stop, from the darkest to the brightest recorded tones.

The silver gelatin negative, for the most part, increases in density by regular amounts for each stop increase in the subject brightness.

In the 16-bit positive digital image, RGB 17 is considered to be the first discernible tone from black and pixel values increase from 16 to 255 by a factor of 1.41 for each stop change in exposure.

This can be confirmed by measuring a monitor with an eight-stop brightness range, correctly set to a gamma of 1.8, using a light meter.

If the positive image increases by a factor of 1.41 for each stop, then for a negative to be an exact inversion of the positive image, it has to decrease from 255 to 16 by a factor of 1.41 for each stop.

Therefore, a correctly inverted digital negative is a negative in which the pixel values decrease by a constant factor for each stop increase in exposure.

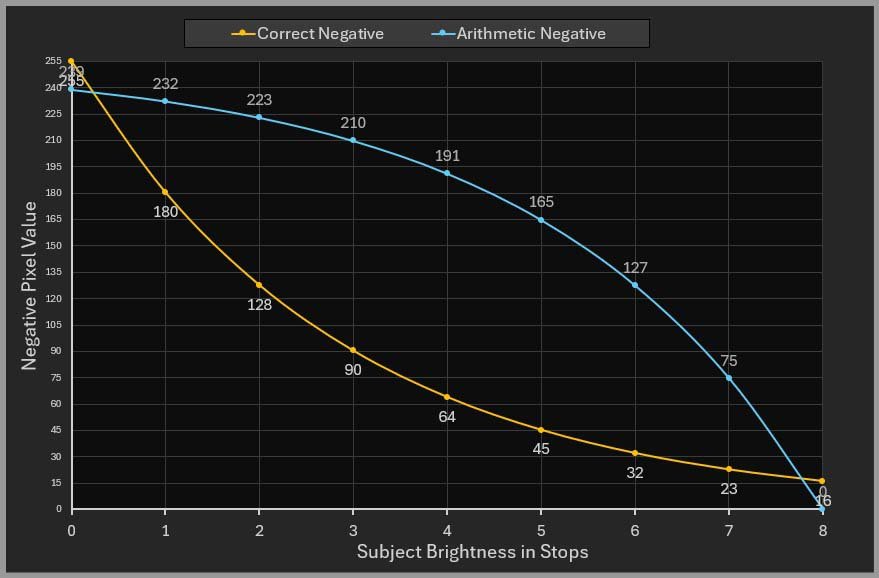

Incorrectly inverted negative showing “underexposed” shadows and truncated highlights

The traditional inverted negative fails because the photo editing programs invert the image by subtracting the positive pixel value from 255.

This creates a negative with very small and uneven factors between the shadow and the midtone stops, and large changes in the highlights. This explains the faint, low-contrast shadows and midtones and the excessive contrast in the highlights of inverted negatives.

Plotting the inverted negative in blue against the correct negative in yellow shows the extent of the problem.

The figure above also shows the constantly changing proportion between the positive exposure stops and negative pixel values. For example, the change between stops one and two is represented by 58 RGB, but the stop change between six and seven is only 9 RGB in the negative.

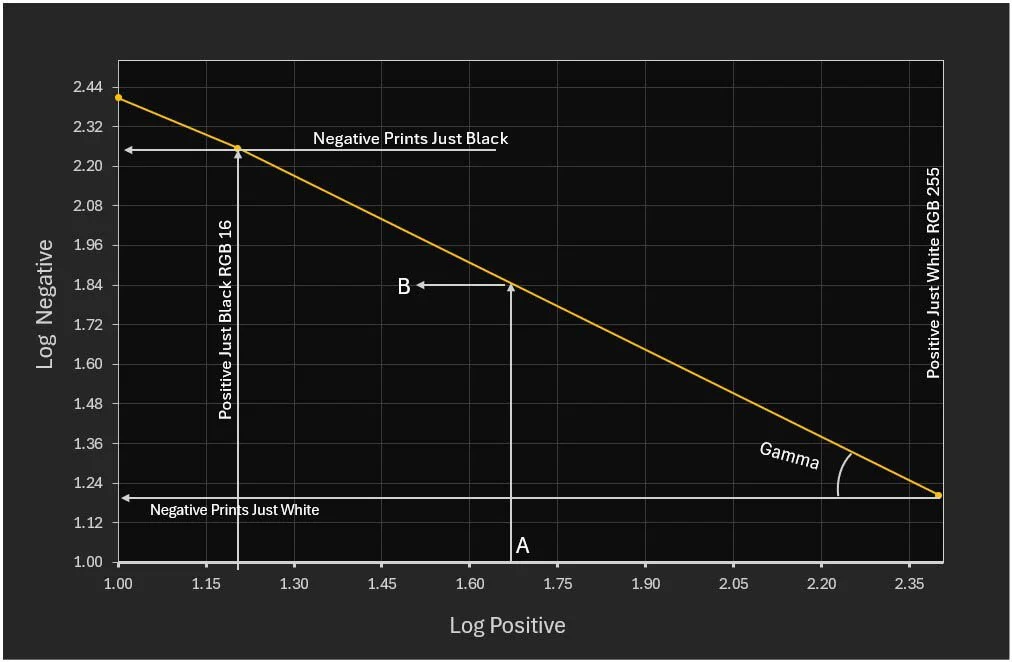

However, if the logarithms of the stop inputs are plotted against the logarithms of the negative outputs, the graph becomes a straight line, producing an inverse proportion between the positive and negative logarithms and making it possible to calculate the negative value B of any positive pixel A.

Correctly inverted negative showing the full range of shadow and highlight tones